Our preference for living in large houses with big yards and tree-lined streets is at direct odds with healthy lifestyles and a healthy planet. It’s well understood by planners that higher levels of density reduce car use and result in homes that are more carbon friendly, through energy efficient design and proximity to centralised energy grids. City dwellers benefit from an ‘urban health advantage’ and can integrate more exercise into their daily lives by commuting on foot or bike. Yet, urban areas have disadvantages, and many of those who have the means relocate to outlying suburbs to access cheaper housing and better schools. Harvard economist, Edward Glaeser, argues that national and local policies should ‘level the playing field’ for cities and starting charging suburbanites for their privileges.

Glaeser’s book, Triumph of the City: How our greatest invention makes us richer, smarter, greener, healthier and happier, examines the effect of policy on development and asserts that in America, government mortgage subsidies, land-use controls and NIMBYs have resulted in the middle-classes leaving cities. This isn’t a uniquely American problem as Glaeser reminds us: ‘Some have suggested that American sprawl represents an English cultural heritage that puts an outsize value on single-family detached houses and backyards’ (2011, p.178). English cities, principally London, suffer very similar fates to cities like New York – only the very wealthy or subsidised social housing tenants can afford to live in the centre of the city.

The Garden Cities movement seeks to bring together the benefits of urban and suburban living, but has not succeeded in making this model a modern norm. Garden Cities would provide affordable well-proportioned homes in walking distance to shops and offices. The 2014 Wolfson Economics Prize was focused on identifying modern conceptualisations of the movement that could help solve England’s housing crisis. The winners’ approach required developing on greenbelt land. This is a hugely contentious undertaking but one that deserves due consideration. Glaeser reminds us that building on greenfield land close to a city is better than creating a self-contained new community (such as the Prince of Wales’ Poundbury estate) detached from existing densely populated areas that can better support amenities and public transportation.

Glaeser claims that NIMBYs who oppose greenfield development often do so with the misguided notion that environmentalism underpins their decision, rather than a preference for the status quo. It was particularly interesting that he highlighted a fault in environmental impact reviews (or assessments in the EU) for not considering the damage to other parts of a county or wider region if the development in question is displaced from one site to another. This issue should be picked up well before the planning application stage in a local area’s development plans, but where these plans are incomplete or not spatially broad enough, the planning system fails to properly direct development toward the most sustainable sites in a region.

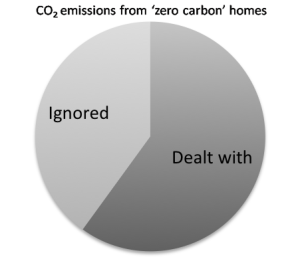

So, where development sprawls and homeowners take up the quintessential Western lifestyle choice to drive everywhere, who should pay the consequences? Glaeser argues: “People who like suburbs should be able to live there, but their choice should be based on the true costs and benefits of suburbanization” (2011, p.268). His solution is to develop a carbon tax that would require energy users to pay for the full costs of their actions. Of particular importance to Glaeser is that Westerners do not hypocritically expect India and China to develop any differently to our sprawling settlements if we cannot ourselves find a way to manage our environmental and social footprint.

Triumph of the City is an extremely thought-provoking book for planners and urbanists. Glaeser takes on sacred figures like Jane Jacobs and highly-regarded movements such as New Urbanism and points out their faults and oversights with evidenced clarity. Some of his interpretations are perhaps overly focused on the economics of places and people, at times overlooking the subtleties of place-making. But maybe his approach is just what we need where traditional town planning methods are not delivering communities that meet today’s global challenges.

Reference:

Glaeser, E., (2011) Triumph of the City: How our greatest invention makes us richer, smarter, greener, healthier and happier, New York, Penguin Books.