After a very long bout of writer’s block, I’ve finally had some inspiration. I’ve written about the importance of central government action and local government decision makers to reduce the UK’s contribution to global warming. But what about the role of planning in the delivery of these aspirational central government policies on the ground?

For local planning authorities, the task of reducing carbon emissions through spatial planning isn’t at all straightforward. Each authority works with different targets (some set in the Regional Spatial Strategy and the London Plan) that are worded slightly differently across the country. The targets are set in development plan document (DPD) policies that are based on evidence supporting the viability of those targets. Leaving the challenge of policy writing aside, the crunch point is that development management officers have to interpret these strategic policies and facilitate development that meets the policy aims. This is the case with all planning policy and delivery, but for climate change policies it’s a little more complicated.

Climate change is a politically charged issue muddled up in people’s minds by the mix of science and ethics. Not everyone agrees that climate change is a problem or that spatial planning is part of the solution. We can probably all agree that planning has an important role to play in housing, transport, parks, etc. But should planning also be responsible for calculating a building’s carbon emissions and a developer’s ability to reduce those by ten to twenty percent? I think not. At the moment, depending on your DPD, this could be in the realm of the planning officer’s duties.

Changes in the Building Regulations Part L and the move to Zero Carbon development could change the game. The ‘Sustainable New Homes – The Road to Zero Carbon’ consultation document (CLG December 2009) gives us a clue for how planning might have a more defined role in reducing emissions, eliminating any overlap with Building Control. Hopefully this would move planners away from Merton Rule type policy and toward policies that would deliver Decentralised Renewable Low Carbon Energy (DRLCE) on a community/neighbourhood scale. I don’t think that development management officers should need to spend time calculating the potential carbon emission reduction from a wind turbine or a photovoltaic cell for every planning application.

This graph from the consultation document shows the steps to achieving a zero carbon home (it looks the same for new non-domestic buildings).

From what I understand, Building Control and the Code for Sustainable Homes would deal with the energy efficiency and the on-site carbon compliance sections, which cover regulated emissions (from space & water heating, lighting, pumps and fans). The allowable solutions would cover the unregulated emissions (anything left over, such as appliances) and this is where planning has a big potential contribution. The allowable solutions are still uncertain but could include things like investments in low and zero carbon community heat infrastructure or exports of low carbon or renewable heat from the development to other developments.

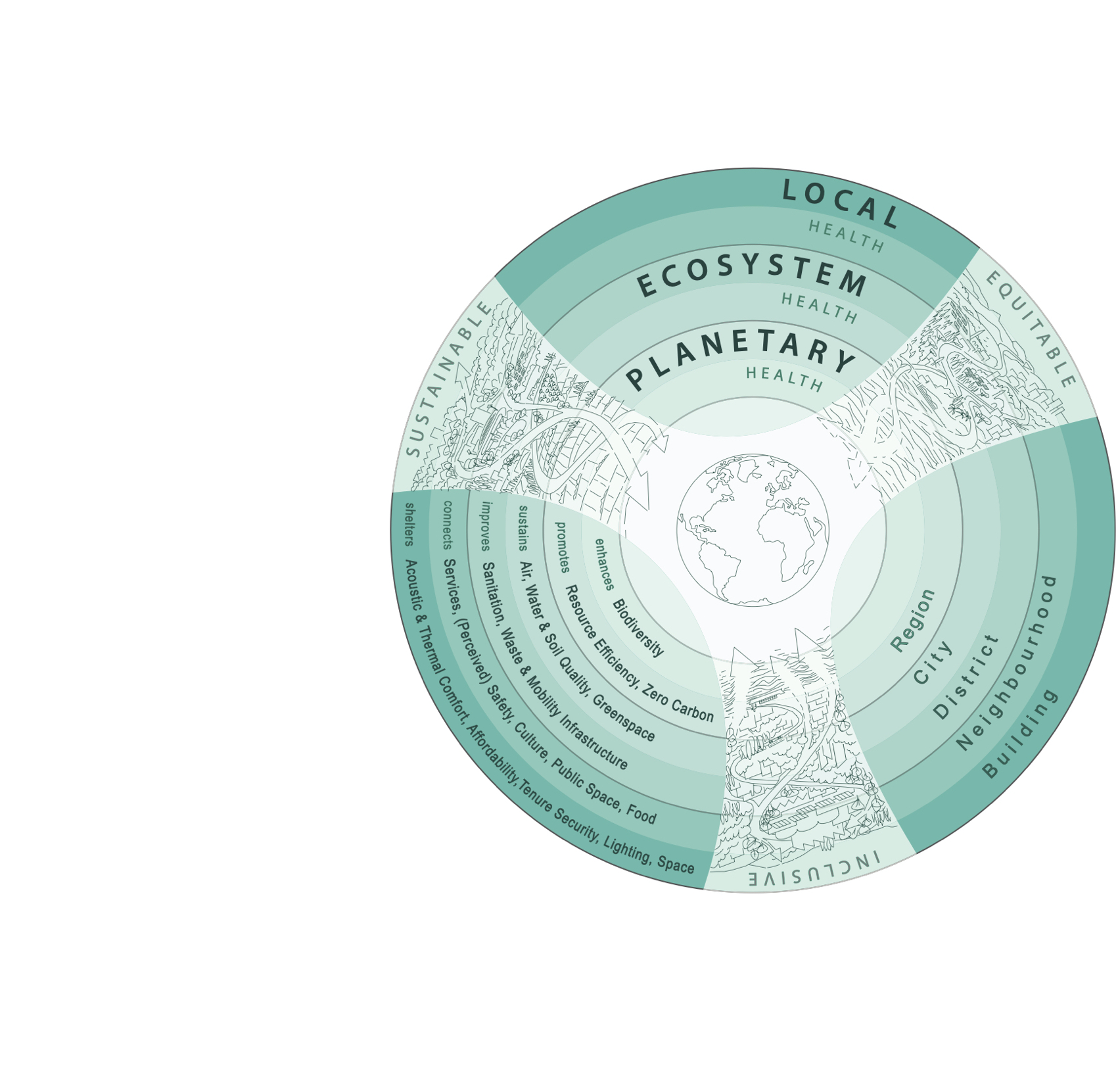

Rather than asking planners to become sustainable energy experts and duplicating work by blurring the responsibilities between building control and planning, we should let planning get on with where it can really add value. Using national datasets and other resources, planners can assess an area’s vulnerability to climate change and the potential for DRLCE (ridiculous acronym, I know). Planners can then use this evidence to work with the local strategic partnership, councillors and the community to make decisions about what an area can do to increase its resilience to climate change.

Opportunities to mitigate against and adapt to climate change should be weaved throughout the core strategy. As the spatial interpretation of the sustainable community strategy, the core strategy should highlight the potential for spatial policies that achieve carbon reduction goals while meeting other community aims, such as reducing obesity and fuel poverty. Development management officers need to be able to communicate the aims of these policies to developers so that the delivery of carbon reduction is seen as a fundamental part of development – fundamentally linked to other community aims – and not an annoying added cost in a recession.