If you had enough money to commission a global architectural practice to design your home, you would also expect them to use sustainable design principles so that your home did not contribute to the number one crisis of our times…right? Apparently not according to anecdotal evidence, but who is to blame for this lack of demand, the client or the industry? And what does this say about our readiness to change our homes for the climate more generally? Where the focus was previously on getting political commitment and funding for decarbonizing the built environment, we need to focus now on helping the public make changes to their homes, and this is a lot harder than we think.

Many companies in residential property development, big and small, aren’t selling sustainable design as core to their product. I came across a marketing piece by a high-end design firm. They were pitching ‘resilient design’ – not regenerative or even sustainable design – but resilient. It was about giving wealthy clients a sense of security and control in a rapidly changing world where overheating, wildfires and power outages are increasingly common. An example from the pitch was that a home would have mechanical cooling most of the time, but natural ventilation would be built in, for use if the power went down. There’s nothing stopping the firm from designing a resilient AND sustainable, even regenerative, home. If budget is not a barrier, these luxury homes could easily have a positive impact for people and planet, but judging by the marketing content, sustainability must not be important to these clients.

I started thinking, who are these clients and how can they disregard their environmental and social responsibilities when they have the financial means to live up to both? But what if they’re just acting on the information that they have, in the world they live in? Common thinking about sustainable homes is that they are a niche and expensive product for lefties. But they don’t have to be expensive. Before the government-led Code for Sustainable Homes was scrapped in the UK in 2015, developers had already found ways to deliver high sustainability at an affordable cost. They also don’t have to be niche. Many cities and countries require high sustainability standards in their building codes. But what about the political element, is sustainable design still seen as a liberal solution, not just a good solution for the problems we all face?

This brings me to the odd social media debates currently raging about heat pumps and stovetops in the USA decarbonization agenda. You don’t have to dig deep to find conspiracy theories and a lot of rage about what people feel they are being ‘forced’ to do in their own homes. So what if people are just acting on the information that they have, in the world that they live in? Relatively rapidly our homes and appliances have become the site of a new kind of fortress building and cultural conflict. In cities and communities that are not in themselves resilient to the impacts of climate change, people with means will buy technologies to keep themselves comfortable. The home fortress in the 2020s is not one with a bomb shelter, but one with a power generator, mechanical cooling and storm shutters. People might not know that their air conditioning unit is making it harder for their neighbours to stay cool. They might feel that the carbon emissions created from their cooling system are an unfortunate but necessary cost to stay safe (in extreme heat) and comfortable (in moderate heat). So lack of information and better solutions are driving current household coping mechanisms, rather than active disregard for the negative impacts of certain technical solutions.

We need to take people along on the journey to homes that are safe for occupants, fit for instability and climate friendly. We have to meet people where they are at not only in terms of money, but also motivation and knowledge. Last summer in the UK heatwave, I took part in some media outreach. On BBC Radio 5 Live, as the academic built environment ‘expert’ I was asked some basic questions about how design could help us stay cool in a heatwave. Reflecting on this now, I overestimated the general level of understanding. I think it’s not just me who has failed to listen and communicate in the right way. A lot of the available information is professionals talking to professionals, not the general public. If we expect people to make changes in their homes to deal with a changing climate, we need to understand the challenges and solutions that they’re currently working with. For example, we need to find out how different people currently cope with heatwaves and how this varies across properties and by age, gender and other factors. Then we can offer help on a scale from free advice on when to close windows all the way up to subsidies for a new heat pump.

If the goals in the US Inflation Reduction Act and similar policies globally are going to be achieved, we need to learn important lessons about getting people to make changes to their homes (not only homeowners but also those who rent or live in public housing). Part of the reason why the UK Green Deal failed to work was a mismatch between the public’s knowledge and willingness to change their home and the government’s support package – specifically a shortfall in dependable suppliers and a lacklustre financing package. There is a huge need to invest in tailored information campaigns and skills development to widen the pool of trusted suppliers. Those of us working on climate change and the built environment need to be more understanding of the reasons that individuals resist changes in their home. It’s not just about publishing infographics, it’s about responding to the cultural, emotional and economic factors that shape the everyday experiences of living through a changing climate.

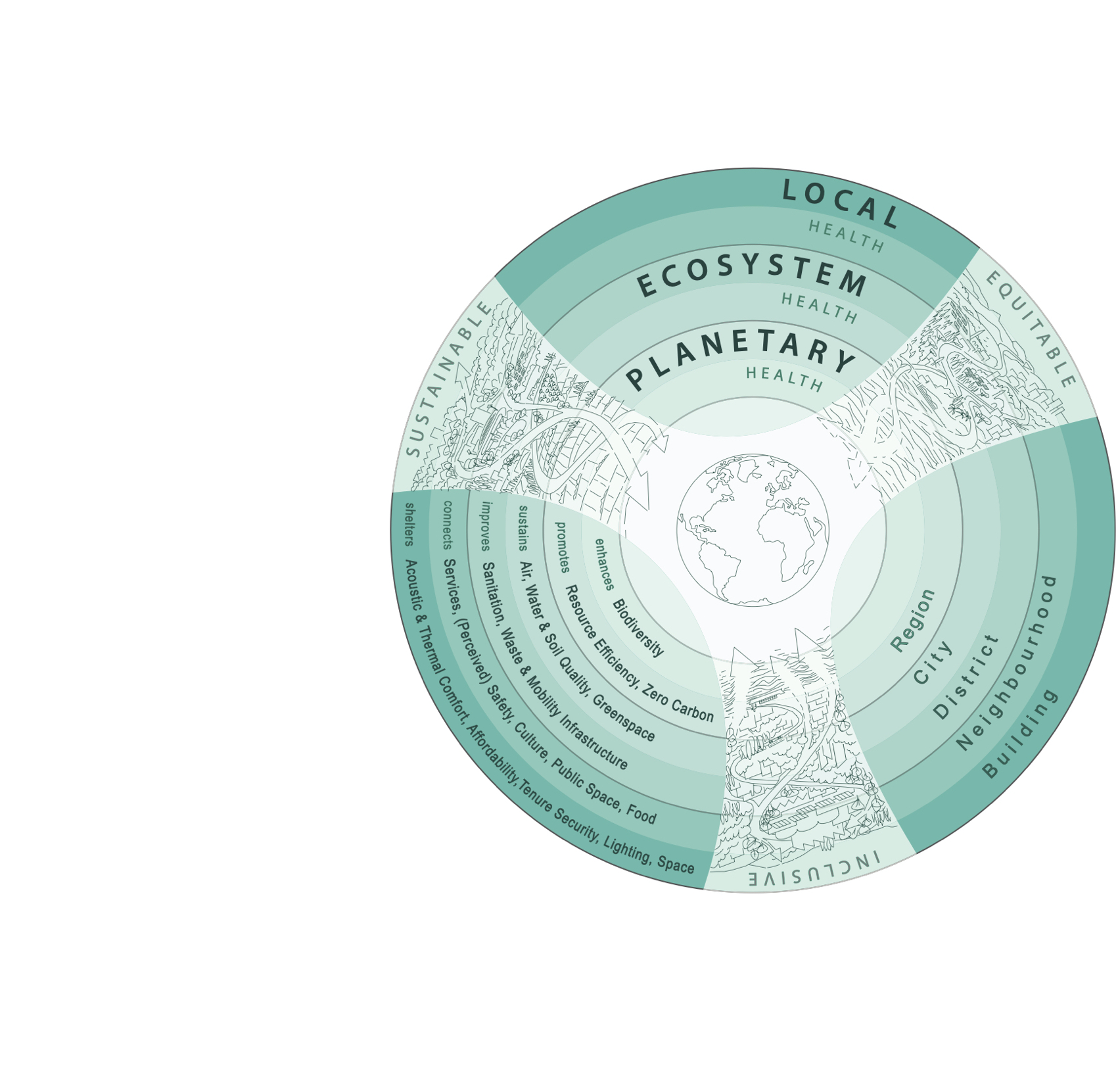

This post is based on the topics discussed in Chapter 9 of Healthy Urbanism.

Image: Outdoor section of a heat pump. Credit Kristoferb, This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 license.